Where is the legal boundary – the line on the plan or that fence?

Generally, the role of a boundary surveyor is to provide an opinion of the intended location of the disputed legal boundary. They will do this by means of the consideration of whatever documentary, photographic and physical evidence is available plus measuring, survey drawings and overlays to plans and aerial photos. Ultimately, if the dispute were to progress that far, it would be for a Court to make a ruling upon the location of the legal boundary but the surveyor must consider all of the technical issues, combine this information with measured survey plans, and provide their opinion.

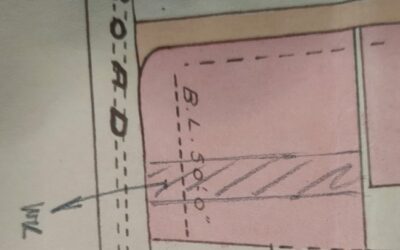

The starting point for the consideration of the intended position of the disputed legal boundary should be conveyance plans, ideally the plan associated with the very first conveyance. This sale which separated one parcel of land into two and thus created the disputed legal boundary is considered to be legally definitive. Unless there are other sales to change this boundary, or a successful claim for adverse possession, once created, this imaginary legal separation line between the two ownerships must (at least generally) remain unchanged on the basis of the legal principle that a person can only sell what they own. So, generally, the aim of the consideration of the true, intended location of the legal boundary is to try to relate that red line on the conveyance ‘paper title’ plan to what now exists on the ground. Sometimes, the intended location of the boundary can be determined with some degree of precision, for example if it lies central to the party wall between two attached houses and then continues as a straight line extrapolation at the front and rear gardens. On other occasions, the red line on the plan might be a poorly drawn thick red line across an open piece of land with few, or possibly no, identifiable fixed reference features.

However, in addition to the use of the paper title conveyance plans (even if relevant plans do still exist which is not always the case), there must also be exploration of current and historic evidence of the location of past physical features in the vicinity of the boundary.

Plan evidence versus physical evidence

Both plan evidence and physical evidence are generally of relevance and importance, with increasing significance and importance of physical evidence inversely related to the clarity and reliability of the plan evidence.

A few key legal cases

There are some important legal judgements which shed some light upon the stance that Courts have taken in the past which, although not binding on future decisions, do add to the case law precedent.

Cameron v Boggiano (2012)

In Cameron v Boggiano (2012), the judgement at appeal concluded that “there could be no confidence in the exact position on the ground of a straight line drawn on a plan that was deficient in detail and exactness in almost every other respect.” In this case, the shortcomings of the plan appear to have included a lack of distance and area measurements, a large thickness of lines drawn onto the plan and the fact that it was based upon an Ordnance Survey plan with associated inherent accuracy limitations. In this case, other comments from the Judge included the following: “In more mundane terms this means that the reasonable layman would go to the property with plan in his hand to see what he is buying. The reasonable layman is not a qualified surveyor or lawyer. If the plan is not, on its own, sufficiently clear to the reasonable layman to fix the boundaries of the property in question, topographical features may be used to clarify and construe it.”

Durden v Aston (2012)

In another case, Durden v Aston (2012), the Court of Appeal concluded that the original Judge had incorrectly placed too much reliance upon the boundary line shown at a Land Registry Title Plan and that insufficient relevance in the Judge’s decision had been given to the position of this line on the ground.

Alan Wibberley Building Ltd v Insley (1999)

In Alan Wibberley Building Ltd v Insley (1999), the judgement from Lord Hoffman set out his opinion which included the following: “The first resort in the event of a boundary dispute is to look at the deeds … The parcels may refer to a plan attached to the conveyance, but this is usually said to be for the purposes of identification only. It cannot therefore be relied upon as delineating the precise boundaries and in any case the scale is often so small and the lines marking the boundaries are so thick as to be useless for the purpose except general identification. It follows that if it becomes necessary to establish the exact boundary, the deeds will almost invariably have to be supplemented by such inferences as may be drawn from topographical features which existed, or may be supposed to have existed, when the conveyances were executed.”

Taylor v Lambert & Lambert (2012)

In Taylor v Lambert & Lambert (2012), the Court reached the conclusion that, in this instance of a contradiction between a plan area measurement and physical features, the plan area evidence could be disregarded in favour of extrinsic evidence.

Burns v Morton (2000)

In Burns v Morton (2000), a boundary fence was replaced by a wall which was sited 6 to 9 inches away from the line of the fence; it seems that neither party disputed that the original fence did mark the boundary before the wall was built in 1979 and that the wall was, therefore, built onto that owners land. Subsequently, the owner prior to the Plaintiff had planted Leylandii trees up to this new wall. The Defendant (on whose land the wall had been built) accessed this area to trim the trees on the assumption that the land between the original fence-line and the wall was still his land. The Plaintiff claimed a trespass.

The Judge ruled that, in fact, the new wall, albeit built 6 to 9 inches away from what was agreed as the original boundary was now to be regarded as the legal boundary and, in this case, a party structure. The Judge stated as follows: “… in order to ascertain whether the defendant has trespassed on the plaintiffs’ land, or indeed pruned trees excessively, it seems to me necessary first to ascertain where the boundary between the premises is. In my judgment, the clear intention of Clause 4, and of the parties who lived on both sides up until 1979 at any rate, was that the fence was the party wall, and whilst I accept that the defendant deliberately built his wall inside the fence line, he must have been aware of the provision of Clause 4 because it appears in his own title or document of title, which is at page 71 in the bundle, and he decided to build this wall without, as I say, any consultation with his neighbours.”

It seems that the relevant clause referred to in the deeds is as follows: “the dividing garden wall or fence (if any) on the North side of the said property and the wall on the South side thereof shall be party walls or fences and maintainable accordingly and any wall or fence on the North shall be erected to the approval of the Architects of the Vendor as to the one half of the thickness thereof on the said piece of land hereby conveyed and as to the other one half thereof on the adjoining land.”

The conclusion of the legal profession in respect of this case appears to be that, bearing in mind the wording within the conveyance, the building of the wall (in approximately the location of the original boundary fence) could be taken to be the subject of an implied agreement that the new wall should be taken to be the boundary. The consequence in this case was that the 6 to 9 inches of land, in effect, moved into the ownership of the Plaintiff.

Brown v Pretot (2011)

The dispute in Brown v Pretot (2011) was one of whether the line on a plan or a fence should be taken as indicating the legal boundary. The transfer plan from the initial sale from the housing developer to the first purchaser was stated to be “for identification only” albeit that this plan’s general accuracy was apparently not disputed. The Court of Appeal concluded that the boundary was not as indicated by the boundary line at the transfer plan but, instead, that the legal boundary was to be taken as the line of a fence which existed at the time of the sale in 1999. If the transfer plan had been accepted by the Court as indicating the boundary, it seems that this would have run through part of a garage. The Judge stated as follows: “There is no reason for preferring a line drawn on a plan as evidence of the boundary to other relevant evidence that may lead the court to reject the plan as evidence of the boundary.”

Cook v J D Wetherspoon Ltd (2006)

In this case, the conveyance plan had annotation that this particular part of the property had a width of 40 feet. However, the scaled width on the plan was 30 feet. The Court decided that reference should be made to physical features which existed at the time of the sale to be able to conclude which was correct, the annotated 40 feet or the scaled 30 feet. In this case, the judgement was that the scaled width was to be taken as the correct dimension.

How Smith Marston can assist

Philip Smith deals with boundary dispute matters for Smith Marston. Philip has well over 20 years of experience of boundary disputes and is an RICS Accredited Expert Witness surveyor for boundary matters. This service is offered nationally from our various regional offices.